Why Brain Hemispheres Fall Asleep at Different Levels and Its Impact

Your brain's hemispheres can operate at different levels of alertness during sleep, particularly in unfamiliar environments. This phenomenon, known as the "first-night effect," occurs when your left hemisphere acts as a night watchman, maintaining a lighter sleep state to respond quickly to potential threats. While your right hemisphere enjoys deeper sleep, the left stays partially alert, leading to poorer sleep quality on the first night in a new place. This split-sleep pattern reflects an evolutionary survival mechanism, similar to how animals can sleep with one hemisphere at a time. Understanding this brain asymmetry opens fascinating possibilities for improving your sleep quality.

Brain Hemispheres and Sleep Patterns

The complexity of brain hemisphere interaction during sleep reveals fascinating differences between species. When you sleep at night, your two brain hemispheres work together, primarily processing information from opposite sides of your body through specialized fiber connections. Your brain cycles between slow-wave and REM sleep phases, following distinct patterns that differ from other species.

In contrast to humans, Pogona lizards display unique hemisphere activity during sleep. Their brain hemispheres synchronize during REM sleep with a 20ms delay between them, and one hemisphere takes the lead over the other in alternating patterns. This exceptional switching is controlled by isthmic circuits located at the midbrain-hindbrain junction. You can observe the importance of these circuits through research showing that when they're damaged, the hemisphere switching stops during REM sleep.

The first major distinction between human and Pogona sleep patterns lies in the duration and organization of sleep phases. While your brain maintains longer, more structured phases, Pogona lizards experience shorter, more equally distributed periods between slow-wave and REM sleep, demonstrating how evolution has shaped different sleep mechanisms across species.

The First Night Effect Explained

Have you ever struggled to sleep well during your first night in a new place? This common experience, known as the first-night effect, isn't just in your head - it's actually your brain's built-in security system at work.

When you're sleeping in an unfamiliar environment, your brain maintains different levels of alertness in each hemisphere. Your left hemisphere acts as a vigilant "night watchman," maintaining lighter sleep and a more active default-mode network compared to your right hemisphere. This asymmetry allows your brain to stay partially alert to potential dangers while still getting some rest.

You'll notice this effect most prominently through your left hemisphere's quick response to unusual sounds and its impact on how long it takes you to fall asleep. The more pronounced this hemispheric difference is, the longer you're likely to spend tossing and turning before drifting off. The good news is that this protective mechanism typically only lasts for one night. By your second night in a new place, the hemispheric asymmetry disappears as your brain recognizes the environment as safe, allowing both hemispheres to achieve deeper, more balanced sleep patterns.

Left Hemisphere as Night Watchman

Looking more closely at your brain's left hemisphere reveals its fascinating role as a biological night watchman during unfamiliar sleep situations. When you're sleeping in a new environment, your left hemisphere stays more alert than your right hemisphere, creating an interhemispheric asymmetry in sleep depth. This natural defense mechanism helps protect you from potential threats while you rest in unfamiliar surroundings.

Your left hemisphere's night watch duties include:

- Maintaining shallower sleep patterns compared to the right hemisphere during your first night

- Responding more quickly to irregular sounds that might signal danger

- Facilitating faster awakening if needed in unfamiliar environments

This protective asymmetry only lasts for your first night in a new place. By the second night, both hemispheres return to normal sleep patterns as your brain becomes more comfortable with the environment. Your left hemisphere's heightened vigilance explains why you might experience poorer sleep quality during your first night in a hotel or different bedroom. It's your brain's way of keeping you safe while you adapt to new surroundings.

Animal Sleep Versus Human Sleep

Remarkably, animals like dolphins and birds possess a unique ability that humans don't share - they can sleep with just one half of their brain at a time. This unique feature, where one brain hemisphere remains alert while the other rests, allows them to maintain constant vigilance against predators while still getting necessary sleep.

While you won't experience this complete HEMISPHERE DURING SLEEP ASSOCIATED pattern, your brain does display a weaker version of this phenomenon. When you're sleeping in an unfamiliar place, your left hemisphere maintains a lighter sleep state to WATCH IN ONE BRAIN for potential dangers. This "first night effect" demonstrates how one hemisphere can remain more alert than the other, though not to the extent seen in animals.

The key difference lies in the degree of asymmetry. While animals can keep one brain hemisphere fully awake, your BRAIN HEMISPHERE DURING SLEEP only shows subtle differences between hemispheres during the first night in a new environment. This partial alertness in your left hemisphere suggests that humans have retained a diluted version of this evolutionary survival mechanism, though we've lost the ability to achieve true unihemispheric sleep like our animal counterparts.

Neural Mechanisms During Asymmetric Sleep

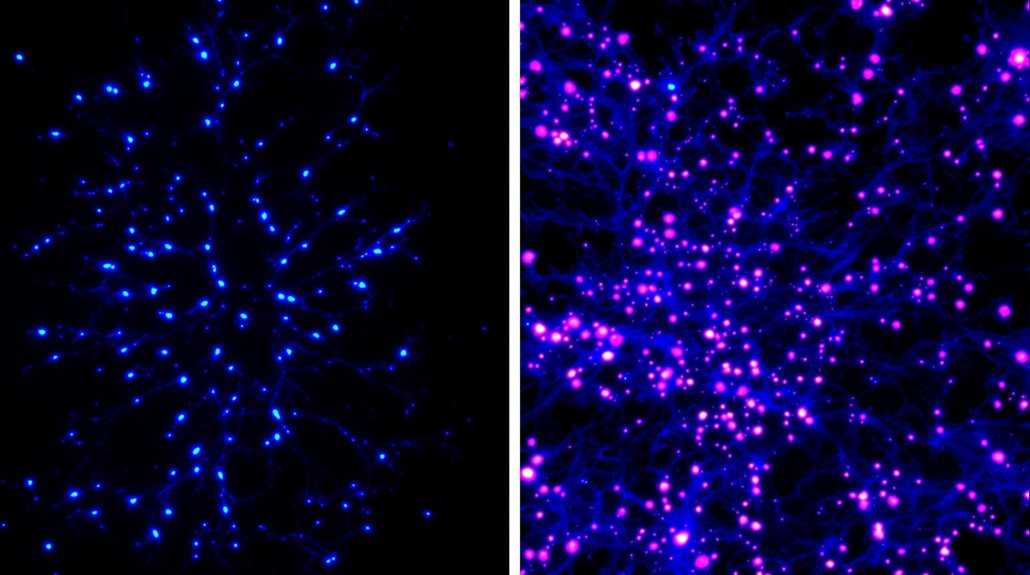

Neural mechanisms underlying asymmetric sleep reveal a fascinating interplay between brain hemispheres. When you're sleeping in a new environment, your brain enters a state of heightened awareness where one hemisphere remains more vigilant than the other. This interhemispheric asymmetry serves as a survival mechanism, allowing your brain to maintain awareness of potential threats while still getting some rest.

- Your brain's structural differences between hemispheres create a fluctuating state where brain networks exhibit varying levels of synchronization, leading to what scientists call a "chimera state" during unihemispheric sleep.

- During the first-night effect, one hemisphere acts as a "night watchman," maintaining higher responsiveness to external stimuli while the other hemisphere enters deeper slow-wave sleep.

- The more pronounced this asymmetry becomes, the longer it'll take you to fall asleep, as your brain balances the need for rest with environmental vigilance.

The relationship between your brain hemispheres during sleep isn't simply about one side being "on" while the other is "off." Instead, it's a complex dance of neural activity that preserves your safety while still allowing you to benefit from restorative sleep.

Environmental Impacts on Sleep Quality

In accordance with recent research, your sleep quality enormously depends on the familiarity of your environment. When you're sleeping in a new place, your brain exhibits a fascinating phenomenon called the first-night effect, where your left hemisphere remains more vigilant than your right. This interhemispheric asymmetry directly affects your sleep depth and how quickly you'll drift off to sleep.

Your left hemisphere's default-mode network becomes more active during your first night in an unfamiliar sleep environment, substantially acting as a night watchman. You'll notice this particularly when there are unusual auditory stimuli - your left hemisphere responds more strongly to these sounds compared to your right. This protective mechanism, while evolutionarily beneficial, can greatly impact your overall sleep quality.

The good news is that you can reduce this sleep disruption by becoming familiar with your environment. As you spend more nights in the same location, the interhemispheric asymmetry diminishes, allowing both brain hemispheres to achieve similar sleep depth levels. This explains why you'll typically sleep better in familiar surroundings, like your own bedroom, compared to hotel rooms or other new locations.

Sleep Research Methods and Findings

Modern research techniques have revolutionized our understanding of sleep patterns and brain activity. When you sleep in an unfamiliar environment, your brain's two hemispheres don't achieve the same level of rest during first sleep sessions. Scientists have uncovered this phenomenon by measuring electrical activity across different brain regions during sleep studies.

Key findings from sleep research include:

- During slow-wave activity, your left and right hemispheres often display varying levels of alertness, with one side remaining more vigilant than the other

- Your brain's asymmetrical sleep patterns are most pronounced when you're sleeping in new environments, serving as a survival mechanism to stay alert to potential threats

- Advanced EEG monitoring shows that complete synchronization between hemispheres typically occurs after multiple nights in the same location

These discoveries wouldn't have been possible without sophisticated monitoring equipment that tracks brain wave patterns throughout the night. By analyzing data from thousands of sleep sessions, researchers have documented how your brain maintains varying levels of consciousness across different regions, particularly during the pivotal first hours of sleep. This research has proven indispensable for understanding sleep disorders and developing more effective treatments.

Survival Advantages of Split Sleep

Split-brain sleep patterns offer several essential survival advantages across different species in the animal kingdom. You'll find this exceptional adaptation in birds, dolphins, and whales, where the left and right hemispheres of their brains can sleep independently. This unihemispheric sleep allows these animals to maintain constant vigilance against predators while still getting necessary rest.

During experimental sessions using advanced neuroimaging, scientists have explored that humans don't experience complete unihemispheric sleep like these animals do. However, you'll notice a similar phenomenon called the first-night effect when sleeping in unfamiliar places. Your left hemisphere remains more alert during this time, much like a natural security system monitoring potential threats while the sleeping brain gets some rest.

This survival mechanism is particularly fascinating in migrating birds, who can literally sleep while flying. They're able to keep one hemisphere awake to traverse and watch for dangers while the other hemisphere cycles through necessary sleep stages, including Rapid Eye Movement. The associated benefits of split sleep patterns demonstrate nature's ingenious solution to balancing the critical needs of rest and survival across various species.

Clinical Applications and Future Research

The astonishing adaptations seen in unihemispheric sleep patterns have sparked promising developments in clinical research and therapeutic approaches. At the Institute for Brain Science, researchers are using magnetic field recordings to understand how interhemispheric asymmetry affects sleep quality. You'll find that these studies, conducted by Wilson ET AL at the Institute of Technology, are revolutionizing our understanding of brain hemisphere synchronization during sleep.

- Scientists can now target specific brain regions to restore balance between hemispheres, potentially treating various sleep disorders

- Advanced computational models help identify vital neural networks involved in unihemispheric sleep regulation

- New therapeutic interventions focus on repairing disrupted interhemispheric communication

You're witnessing a change in how we approach sleep disorders. By understanding the complex relationship between sleep, memory, and cognition, researchers can develop more effective treatments. They're particularly interested in how interhemispheric asymmetry influences various neurological and psychiatric conditions. Future research will likely focus on developing targeted interventions that can modify brain network synchronization, potentially leading to breakthrough treatments for sleep-related disorders.